Authors:

David M. Francis, The Ohio State University

Heather L. Merk, The Ohio State University

Introduction

Molecular markers have great potential to assist plant breeders in development of improved varieties by complementing phenotypic selection. This module provides an overview of molecular markers. Technology used for genotyping is rapidly changing, requiring us to think beyond markers as bands on a gel.

The following links provide background information:

- DNA as a biochemical entity and data string

- Traditional view of molecular markers

- Assays for molecular marker genotyping

- An example of marker-assisted selection

Although previously conceptualized as “bands on a gel”, molecular marker data is increasingly in the form of numbers on a spreadsheet, regardless of type of marker, as discussed below. This trend will continue to increase as the volume of sequence data increases. With the continuing decline in the cost of DNA sequencing, the volume of sequence data is increasing exponentially. We now often think of two types of molecular markers; size variants and sequence variants. Both of these types of markers are discussed below.

Molecular Markers as Size Variants

One type of mutation is the insertion/deletion class of polymorphism. These mutations can be detected as fragment-length differences. A special class of insertion/deletion polymorphisms are the Simple Sequence Repeat (SSR) polymorphisms, also called microsatellites. These polymorphisms occur in short sequences of repeated DNA. For example, one variety may have the sequence GAGCAACAACAACG which has three repeats of CAA (or AAC, depending where you start counting from). A second variety may have the sequence GAGCAACAACAACAACAACG where the trinucleotide CAA is repeated five times. SSRs typically consist of di-, tri- or tetra-nucleotide repeats. They are highly variable in genomes, with mutation rates that are up to 10-fold higher than SNPs. The increased mutation rate is thought to occur due to slipped strand mis-pairing (slippage) during DNA replication resulting in two to 20 alleles at a given locus, unlike SNPs which typically have only two alleles. As a result, SSRs have greater information content (polymorphism) than SNPs for a given marker, although their frequency in the genome is much less than SNPs. SSRs are rarely found in exons. These mutations therefore provide DNA markers that are highly variable, dispersed throughout the genome, and easily detected as size polymorphisms as long as the detection method can distinguish -2, -3, or -4 base differences.

Assaying Size Variants:

Molecular Markers as Sequence Variants

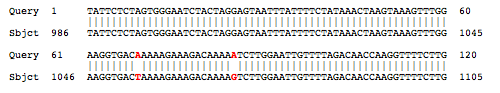

By comparing DNA sequences between two or more plant varieties (or within a heterozygous plant), we can identify sequence variants as single base pair substitutions or single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). These are found thoughout the genome, including in genes. When SNPs are located in genes they may change a protein and therefore the expression of a trait (phenotype). In these cases, the SNP causes a non-synonymous substitution. SNPs may also change the expression of a gene if they occur in promoters or other regulatory sequences. Detecting differences relies on comparative biology, as the alignment of the PSY1 sequence from the tomato genotype “Red Setter” with the VRT-32-1 indicates. The A/T change at position 69 and the A/G mutation at position 85 (Fig.1) represent sequence variations that can be used for marker development.

Figure 1. Alignment of a portion of the tomato PSY1 gene between the query sequence for “Red Setter” and the subject sequence for VRT-32-1. The alignment was produced using the NCBI align2seq function in BLAST. Alignment provided by David Francis, The Ohio State University.

Assaying Sequence Variation:

Additional Resources

For a thorough introduction to molecular markers, see Chapter 3 (p. 45–83), Introduction to Genomics, in:

- Liu, B. H. 1998. Statistical genomics: Linkage, mapping, and QTL analysis. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

For an introduction to molecular markers, linkage mapping, QTL analysis, and marker-assisted selection written for professional plant breeders, see:

- Collard, B.C.Y., M.Z.Z. Jaufer, J. B. Brouwer, and E.C.K. Pang. 2005. An introduction to markers, quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping and marker-assisted selection for crop improvement: The basic concepts. Euphytica 142: 169–196. (Available online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10681-005-1681-5) (verified 29 Dec 2010).

Funding Statement

Development of this page was supported in part by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) Solanaceae Coordinated Agricultural Project, agreement 2009-85606-05673, administered by Michigan State University. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the United States Department of Agriculture.

PBGworks 879